How I Study Open Source Community Growth with dbt

Most organizations spend at least some of their time contributing to an open source project. 100% of them, though, depend in some way on the output of open source communities.

In fact we all do. The work of communities can be found everywhere - in the cell phone that wakes you up, the machine that makes your coffee, the car that drives you to get better coffee, the magic app that brings you dinner, and the television that lulls you back to sleep. It's your entire day, even if you aren't a software engineer. Call me weird, but I think everyone should be interested in how open source communities grow and operate.

Why I Care About Open Source Adoption

There are two communities that my colleagues and I have a particular curiosity in: OpenLineage and Marquez. We build a product based on the standards, conventions, and capabilities that are created there, and at least 70% of our engineering time is spent in contribution. Understanding how these communities grow and evolve, and how our behavior affects them, is important to each of us.

In many organizations it's important to measure the results of ongoing investment in open source projects, especially when dealing with stakeholders who favor quantitative proof. Often, this is framed in terms of popularity and adoption - i.e., "how many people use our stuff" and "how many people love it". A chart showing strong adoption of a project is likely to make hard conversations easier...and a hockey stick might just lead to a stronger round of funding.

But there are tactical uses for this data as well. Consider these scenarios:

- Docker pulls of a particular image have unexpectedly dropped in frequency

- A vulnerability has been fixed in a Python module, but people are still downloading the old version for some reason

- An engineer who is about to go on sabbatical is the most active participant on Slack

These are all situations that require investigation and action, and can only be discovered with up-to-date information on open source community activity. It has become essential for teams like ours - perhaps even as essential as an accurate sales pipeline forecast. Fortunately, this information is easy to find.

In most cases, the numbers I'm looking for are on a web page, just a few clicks away. I can visit the GitHub page for a project and see the number of stars, or look at a package on PyPI when I need to know how many downloads it's gotten. But it's hard to get a sense of how a thing behaves by looking at its current state. Instead, you have to watch it move! You need to collect the data that's important to your business and study how it changes over time.

That's why I built a mini-warehouse for studying community growth. Several times a day I gather information about the OpenLineage and Marquez communities from different data sources. My models process the data so that it's easy to perform analysis and spot trends.

In this post, I'll walk you through our stack and sources. Then I'll show you how I track engagement across Slack, GitHub, Docker Hub, and PyPI, using a warehouse built with BigQuery, dbt, OpenLineage and Superset.

The Tool Stack

I am a copy-and-paste coder, which means that starting with an empty screen is difficult for me. So it was important that I built everything using standard tools with established communities and plenty of examples.

Here are the tools I chose to use:

-

Google Bigquery acts as the main database, holding all the source data, intermediate models, and data marts. This could just as easily have been Snowflake or Redshift, but I chose BigQuery because one of my data sources is already there as a public dataset.

-

dbt seeds data from offline sources and performs necessary transformations on data after it's been loaded into BigQuery.

-

OpenLineage collects data lineage and performance metadata as models run, so I can identify issues and find bottlenecks. Also, to be the subject ecosystem for this study :)

-

Superset visualizes and analyzes results, creates dashboards, and helps me communicate with stakeholders.

Data Sources & Metrics

I decided to start small, with just four data sources: Slack, GitHub, Docker Hub, and PyPI. This gives me a good sense for both the activity in and adoption of the projects over time.

For starters, I want to know how much conversation is occurring across the various channels and communities we participate in. Our communities use Slack, so the number of messages over time (by user) is what I'm looking for. When there's an unexpected boost in activity, I'd like to be able to study the change in its historical context. I need to be able to view a list of the most active users, updated automatically. When new members join, I want to understand how their activity affects the community.

There are a ton of metrics that can be tracked in any GitHub project — committers, pull requests, forks, releases — but I started pretty simple. For each of the projects we participate in, I just want to know how the number of GitHub stars grows over time, and whether the growth is accelerating or flattening out. This has become a key performance indicator for open source communities, for better or for worse, and keeping track of it isn't optional.

Finally, I want to know how much Marquez and OpenLineage are being used. It used to be that when you wanted to consume a bit of tech, you'd download a file. Folks like me who study user behavior would track download counts as if they were stock prices. This is no longer the case; today, our tech is increasingly distributed through package managers and image repositories. Docker Hub and PyPI metrics have therefore become good indicators of consumption. Docker image pulls and runs of python -m pip install are the modern day download and, as noisy as these metrics are, they indicate a similar level of user commitment.

To summarize, here are the metrics I decided to track (for now, anyway):

- Slack messages (by user/ by community)

- GitHub stars (by project)

- Docker Hub pulls (by image)

- PyPI downloads (by package)

Getting raw data into BigQuery

The first step was to get all of my raw data into BigQuery. This was the messiest part of the entire operation, without question. Let's dig into each data source one at a time.

Slack

Loading in the raw data

It wasn't immediately clear how to get a message count from each of the Slack communities. The Slack API can provide some of what I need, but I chose instead to use Zapier to load messages into BigQuery in real time.

Zapier is an event-based system that can be used to automate random tasks. It has a collection of connectors with common toolchain components and a straightforward interface for designing actions. I implemented a basic Zap that triggers on each new Slack message, storing a copy of the message in a BigQuery table.

Before creating the Zap, I created a table called slack_messages to act as a destination. The schema is as follows:

CREATE TABLE `openlineage.metrics.slack_messages`

(

message_time TIMESTAMP NOT NULL,

domain STRING NOT NULL,

username STRING,

realname STRING,

email STRING,

channel STRING,

permalink STRING,

text STRING

)

Next I created two separate Zaps using the "New Public Message Posted Anywhere in Slack" trigger, one for the OpenLineage community and one for the Marquez community. I chose the "Create Row in Google BigQuery" action, and mapped across each of the fields the schema required.

After turning the two Zaps on, I was able to verify that new messages were appearing in the slack_messages table.

Setting up dbt sources

To make dbt aware of this new table, I created a new models/schema.yml file containing the following:

sources:

- name: metrics

database: openlineage

schema: metrics

tables:

- name: slack_messages

From this, dbt knows to grab the schema for these tables from BigQuery during generation of the documentation website and store it in catalog.json for later use. For more information about defining sources, take a look at the Sources page in the dbt docs.

Explicitly defining external data sources in dbt was important to me for two reasons:

- It allows us to use the jinja

source()andref()functions to refer to these tables within our models, as opposed to hardcoding the table names. - It ensures that the schemas are included in

catalog.jsonwhendbt docs generateis run, which is critical for collecting and tracing data lineage. I need this information so that it can be transmitted to OpenLineage during the run cycle.

GitHub

Loading in the raw data

Getting a current GitHub star count into BigQuery wasn't terribly difficult, since there is a public API that provides it.

I created a short Python script inside a new loaderscripts/ directory in my project to pull the latest star count from the GitHub API and load it into BigQuery. This script is called at the beginning of each pipeline run, currently as part of my container's entrypoint.sh. Here are the important bits:

dataset_ref = client.dataset('metrics')

table_ref = dataset_ref.table('github_stars')

table = client.get_table(table_ref)

now = int(time.time())

for project in projects:

url = 'https://api.github.com/repos/' + project

response = requests.get(url)

watchers = response.json()['watchers']

client.insert_rows(table, [(now,project,watchers)])

You can see the script in its entirety here. It ensures that the latest GitHub star count is always available before the run cycle begins.

Before running the script, I created a table called github_stars to act as a destination. The schema:

CREATE TABLE `openlineage.metrics.github_stars`

(

timestamp TIMESTAMP,

project STRING,

stars INT64

)

Setting up dbt sources

To make dbt aware of this new github_stars table, I added it to the list of tables in models/schema.xml:

sources:

- name: metrics

database: openlineage

schema: metrics

tables:

- name: github_stars

This is an effective way to track stars from now on, but can't be used to populate any historical data. Fortunately, there are a few ways to get the complete star history for a project. I used this tool to download CSVs of GitHub star history for each of the projects. I combined them into a single file and placed it in data/github_daily_summary_history.csv as a seed file.

The schema for this data must be explicitly defined. I did this by adding a section to dbt_project.yml file with the following:

seeds:

openlineage_elt:

github_daily_summary_history:

+column_types:

day: date

project: string

stars: integer

When dbt seed is run, a table will be created with the star history. Being explicit about column types in this way ensures that each field is parsed as the intended type.

DockerHub

Loading in the raw data

For Docker Hub, I took a similar approach. There's an API that provides the total number of pulls each image has had over its entire history. I wrote another simple script in loaderscripts/ to poll the API and load the count into BigQuery. It is very similar to the GitHub script, with only the block at the end differing:

for image in images:

url = 'https://hub.docker.com/v2/repositories/' + image

response = requests.get(url)

pull_count = response.json()['pull_count']

client.insert_rows(table, [(now,image,pull_count)])

You can see the script in its entirety here. Like the GitHub loader script, this is executed immediately before the dbt run cycle begins.

Just as I did with the GitHub loader script, I created a table called dockerhub_pulls. The schema is as follows:

CREATE TABLE `openlineage.metrics.dockerhub_pulls`

(

timestamp TIMESTAMP,

image STRING,

pull_count INT64

)

Setting up dbt sources

Again, to make dbt aware of this new dockerhub_pulls table, I added it to the list of tables in models/schema.xml:

sources:

- name: metrics

database: openlineage

schema: metrics

tables:

- name: slack_messages

- name: github_stars

- name: dockerhub_pulls

PyPI

PyPI download stats are available as a public data set in BigQuery, so they are easy to work with. There is a file_downloads table that contains one row per download, which is ideal for my purposes. However, it's a lot of data to be working with, and I only care about a little bit of it.

I decided that this situation called for a small slice of PyPI: a table that only contains rows for the packages I am studying, one that I can point a greedy dashboarding tool at without blowing up my Google Cloud bill.

To carve this slice, I first added the source table from the BigQuery public data set to models/schema.xml:

sources:

- name: metrics

database: openlineage

schema: metrics

tables:

- name: slack_messages

- name: github_stars

- name: dockerhub_pulls

- name: pypi

database: bigquery-public-data

schema: pypi

tables:

- name: file_downloads

Then, I created an incremental model in models/pypi_downloads.sql that pulls the target rows and columns from the source table. I used an incremental model so it could be re-run periodically to update my slice with the latest rows from the source table:

{{

config(

materialized='incremental'

)

}}

select timestamp, country_code, url,

file.project as project, file.version as version,

file.type as type

from {{ source('pypi', 'file_downloads') }}

where (

file.project = 'marquez-python'

or file.project = 'marquez-airflow'

)

and timestamp > TIMESTAMP_SECONDS(1549497600)

{% if is_incremental() %}

and timestamp > (select max(timestamp) from {{ this }})

{% endif %}

Creating data models

So! I had figured out how to load all the raw data into BigQuery, but I wasn't done yet. Dashboarding tools tend to want data structured in predictable ways, and that means having clear measures and dimensions (almost always with one of the dimensions being a unit of time). I created several dbt models to cajole everything into the proper shape.

Slack

For Slack, I had a simple transformation to do. The slack_messages table contains one row per message sent. What I needed, instead, was one row per user, per community, per day; the only measure I track currently is the number of messages sent.

To create this table, I built a new model in models/slack_daily_summary_by_user.sql containing:

select

DATE_TRUNC(DATE(message_time), DAY) AS day,

domain,

username,

count(*) AS messages

from {{ source('metrics', 'slack_messages') }}

group by day, domain, username

GitHub

For GitHub, the challenge is that there are two inputs: github_stars, which is populated by the loader script, and github_daily_summary_history, which is loaded from a CSV file. Both of these sources contain a date, a project, and a star count. In both cases there is the possibility of multiple data points per day.

What I want, instead, is a single table with one row per day per GitHub project. I created models/github_daily_summary.sql containing:

with combined_stars as (

select DATE_TRUNC(DATE(timestamp), DAY) AS day, project, stars

from {{ source('metrics', 'github_stars') }}

union all

select * from {{ ref('github_daily_summary_history') }}

)

select day, project, max(stars) AS stars

from combined_stars

group by day, project

Docker Hub

The Docker Hub data requires very little transformation. However, for consistency I decided to create a summary table containing the maximum value recorded for each image on a given day. To accomplish this, a new models/dockerhub_daily_summary.sql file was required:

{{

config(

materialized='view'

)

}}

select

DATE_TRUNC(DATE(timestamp), DAY) AS day,

image, max(pull_count) AS total_pulls

from {{ source('metrics', 'dockerhub_pulls') }}

group by day, image

I decided to make this a view, since the source table is already pretty svelte and the transformation involved is lightweight. In the future, I'd like to calculate a new_pulls field that contains the difference between the current total_pulls and the previous day's value. Once I build that, I'm likely to change this model into a table.

PyPI

Finally, the PyPI data requires a simple model to count the number of daily downloads per package, models/pypi_daily_summary.sql:

select

DATE_TRUNC(DATE(timestamp), DAY) AS day,

project, version, count(*) AS num_downloads

from {{ ref('pypi_downloads') }}

group by day, project, version

Configuring OpenLineage

In order to collect lineage metadata as the models run, I used the OpenLineage wrapper script. This script collects lineage metadata from files generated by dbt during the run, emitting OpenLineage events to a metadata server.

Having this metadata allows me to study the flow of data as it changes over time. This might seem like overkill for such a small, basic pipeline, but I've got a feeling it won't stay that way for long. It's best to establish good practices early.

To make sure the script and OpenLineage client libraries were installed in my Python virtual environment (hey, folks, always use a virtual environment!) I ran:

% pip3 install openlineage-dbt

Marquez is an OpenLineage-compatible metadata server and lineage analysis tool. I spun up an instance using its docker/up.sh script:

% git clone git@github.com:MarquezProject/marquez.git

% cd marquez

% ./docker/up.sh -d

Finally, I set the OPENLINEAGE_URL environment variable to the location of my Marquez server:

% export OPENLINEAGE_URL=http://localhost:5000

Running the Pipeline

The OpenLineage integration pulls some important metadata from target/catalog.json, which is created by dbt when docs are generated. So it's necessary to do so before running models:

% dbt docs generate

Running with dbt=0.21.0

Found 7 models, 0 tests, 0 snapshots, 0 analyses, 184 macros, 0 operations, 2 seed files, 4 sources, 0 exposures

18:41:20 | Concurrency: 1 threads (target='dev')

18:41:20 |

18:41:20 | Done.

18:41:20 | Building catalog

18:41:31 | Catalog written to /Users/rturk/projects/metrics/target/catalog.json

Next, I ran each of the scripts inside the loaderscripts/ directory to populate GitHub stars and Docker Hub pulls from their respective APIs:

% for x in loaderscripts/*.py; do python3 $x; done

Then, to create the github_daily_summary_history table with the contents of the file in data/:

% dbt seed

Running with dbt=0.21.0

Found 7 models, 0 tests, 0 snapshots, 0 analyses, 184 macros, 0 operations, 2 seed files, 4 sources, 0 exposures

18:40:45 | Concurrency: 1 threads (target='dev')

18:40:45 |

18:40:45 | 1 of 2 START seed file metrics.github_daily_summary_history.......... [RUN]

18:40:49 | 1 of 2 OK loaded seed file metrics.github_daily_summary_history...... [INSERT 2000 in 4.60s]

18:40:49 | 2 of 2 START seed file metrics.slack_daily_summary_history........... [RUN]

18:40:53 | 2 of 2 OK loaded seed file metrics.slack_daily_summary_history....... [INSERT 316 in 4.07s]

18:40:53 |

18:40:53 | Finished running 2 seeds in 9.48s.

Completed successfully

Done. PASS=2 WARN=0 ERROR=0 SKIP=0 TOTAL=2

Finally, to run the models and pass lineage metadata to my local instance of Marquez:

% dbt-ol run

Running OpenLineage dbt wrapper version 0.3.1

This wrapper will send OpenLineage events at the end of dbt execution.

Running with dbt=0.21.0

Found 7 models, 0 tests, 0 snapshots, 0 analyses, 184 macros, 0 operations, 2 seed files, 4 sources, 0 exposures

18:44:15 | Concurrency: 1 threads (target='dev')

18:44:15 |

18:44:15 | 1 of 7 START view model metrics.dockerhub_daily_summary.............. [RUN]

18:44:16 | 1 of 7 OK created view model metrics.dockerhub_daily_summary......... [OK in 0.98s]

18:44:16 | 2 of 7 START table model metrics.github_daily_summary................ [RUN]

18:44:19 | 2 of 7 OK created table model metrics.github_daily_summary........... [CREATE TABLE (1.6k rows, 79.1 KB processed) in 3.03s]

18:44:19 | 3 of 7 START incremental model metrics.pypi_downloads................ [RUN]

18:44:44 | 3 of 7 OK created incremental model metrics.pypi_downloads........... [MERGE (1.7k rows, 7.2 GB processed) in 25.10s]

18:44:44 | 4 of 7 START view model metrics.slack_daily_summary.................. [RUN]

18:44:45 | 4 of 7 OK created view model metrics.slack_daily_summary............. [OK in 0.81s]

18:44:45 | 5 of 7 START view model metrics.slack_daily_summary_by_user.......... [RUN]

18:44:46 | 5 of 7 OK created view model metrics.slack_daily_summary_by_user..... [OK in 0.87s]

18:44:46 | 6 of 7 START table model metrics.pypi_daily_summary.................. [RUN]

18:44:49 | 6 of 7 OK created table model metrics.pypi_daily_summary............. [CREATE TABLE (35.9k rows, 4.7 MB processed) in 3.04s]

18:44:49 | 7 of 7 START view model metrics.daily_summary........................ [RUN]

18:44:50 | 7 of 7 OK created view model metrics.daily_summary................... [OK in 0.87s]

18:44:50 |

18:44:50 | Finished running 4 view models, 2 table models, 1 incremental model in 35.55s.

Completed successfully

Done. PASS=7 WARN=0 ERROR=0 SKIP=0 TOTAL=7

Emitting OpenLineage events: 100%|████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████| 14/14 [00:01<00:00, 7.89it/s]

Emitted 16 openlineage events

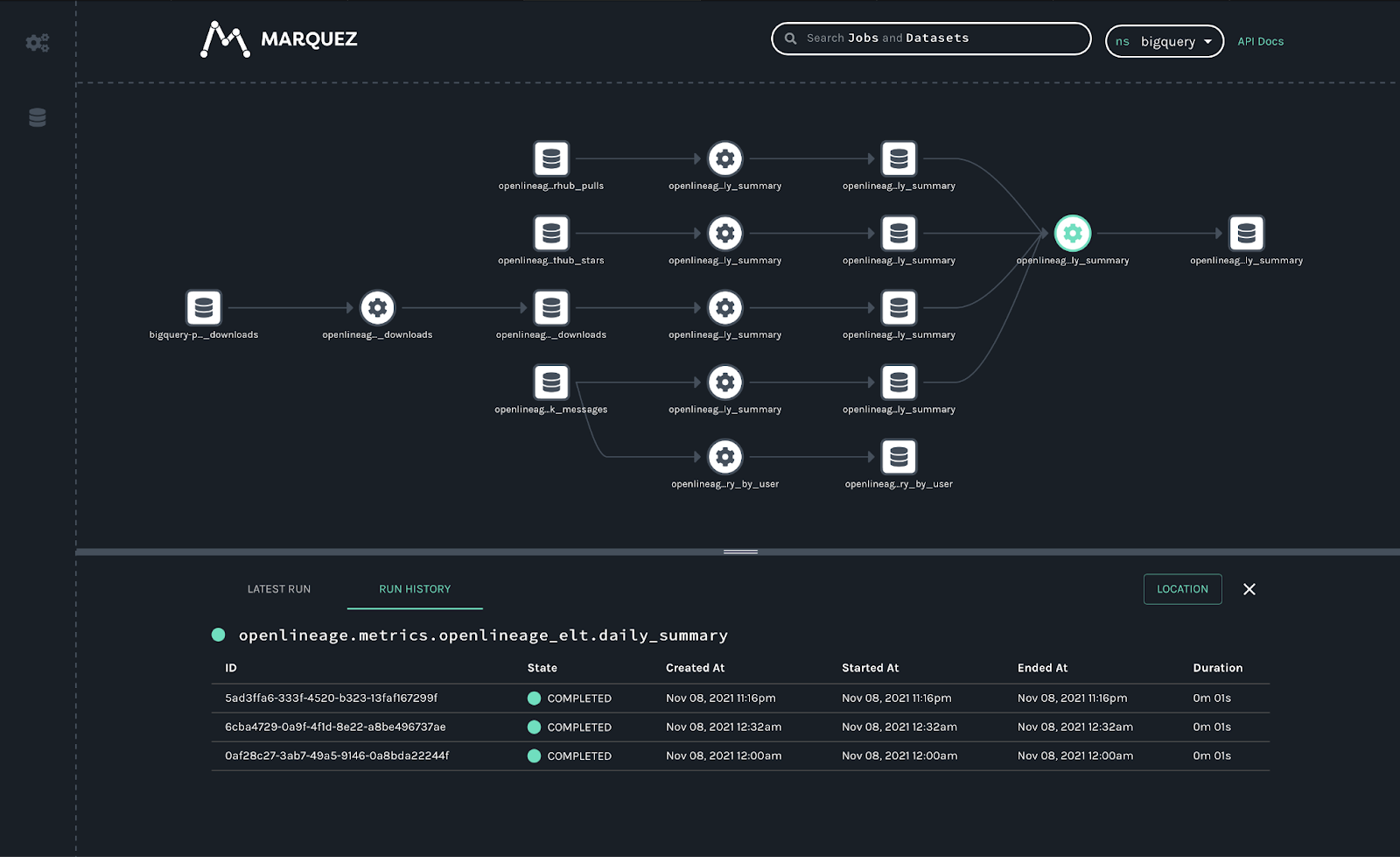

A lineage graph of the entire pipeline can now be viewed in Marquez, which shows the relationships between datasets and provides detail about the run history.

Visualizing the Results

This is the simplest part, by far. Since we have a set of tables with clearly-defined measures and dimensions, getting everything working in a system like Apache Superset is straightforward.

Configuring the data source and adding each table to a Preset Workspace was easy. First, I connected my BigQuery database by uploading a JSON key for my service account.

Once the database connection was in place, I created datasets for each of my *_daily_summary tables by selecting the database/schema/table from a dropdown.

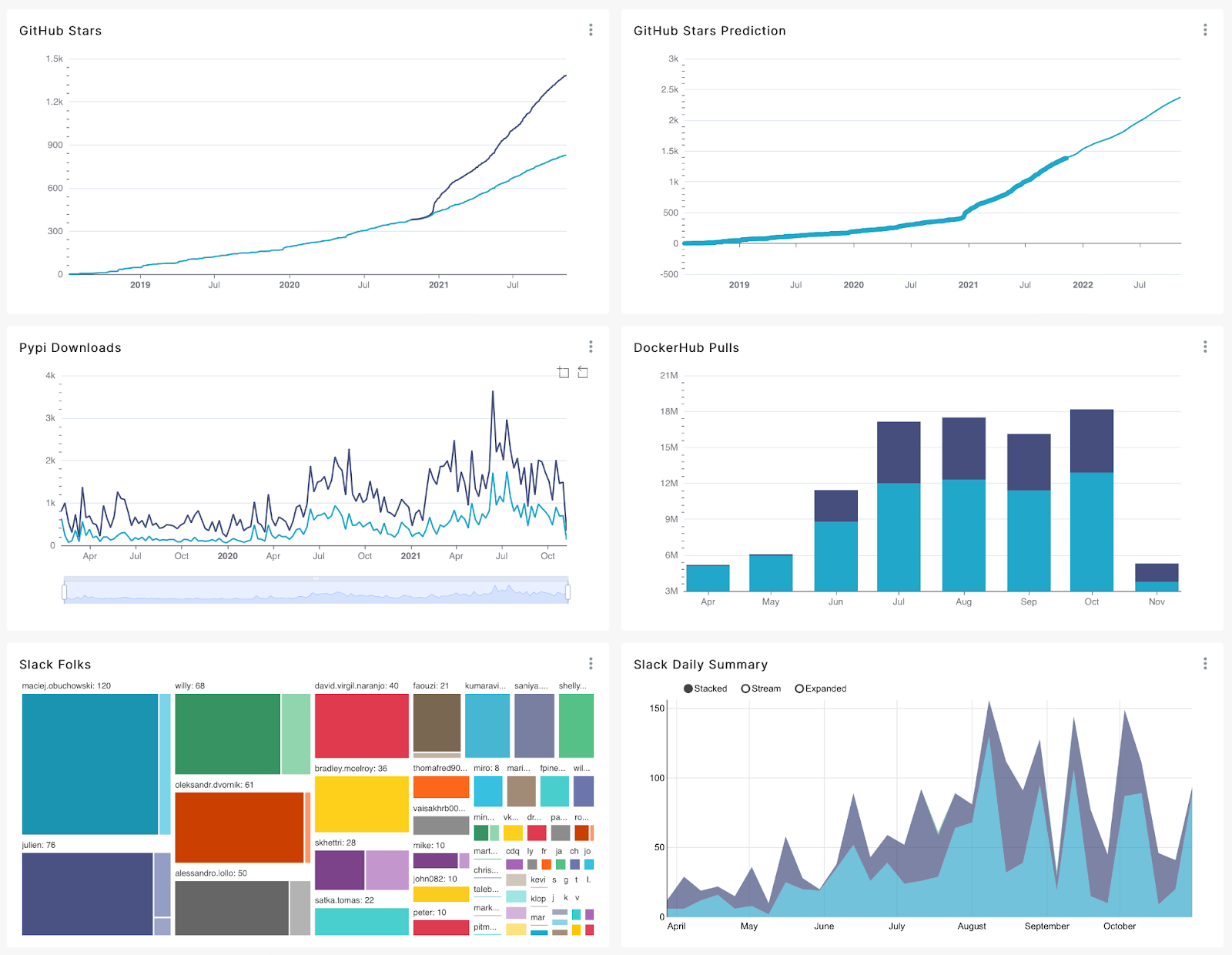

With the database and datasets configured, I was able to use the charting interface to explore the various measures and dimensions in the warehouse. After about fifteen minutes, I had created a dashboard that shows the evolution of the communities where my colleagues and I do our work.

This overall view is interesting - it suggests acceleration in activity across every channel during the summer of 2021, which makes a lot of sense. That is when the first release of OpenLineage happened, and also when a few talks and podcasts were released. Things have slowed down as the holiday approaches, which also checks out. Unless you're in the retail business, that kind of thing happens.

Indeed, you can see a familiar pattern happen every year on the PyPI chart. That indicates at least one thing: CI/CD systems aren't responsible for all of those package downloads. The trend has too much humanity baked into it, too many calendar-influenced peaks and valleys.

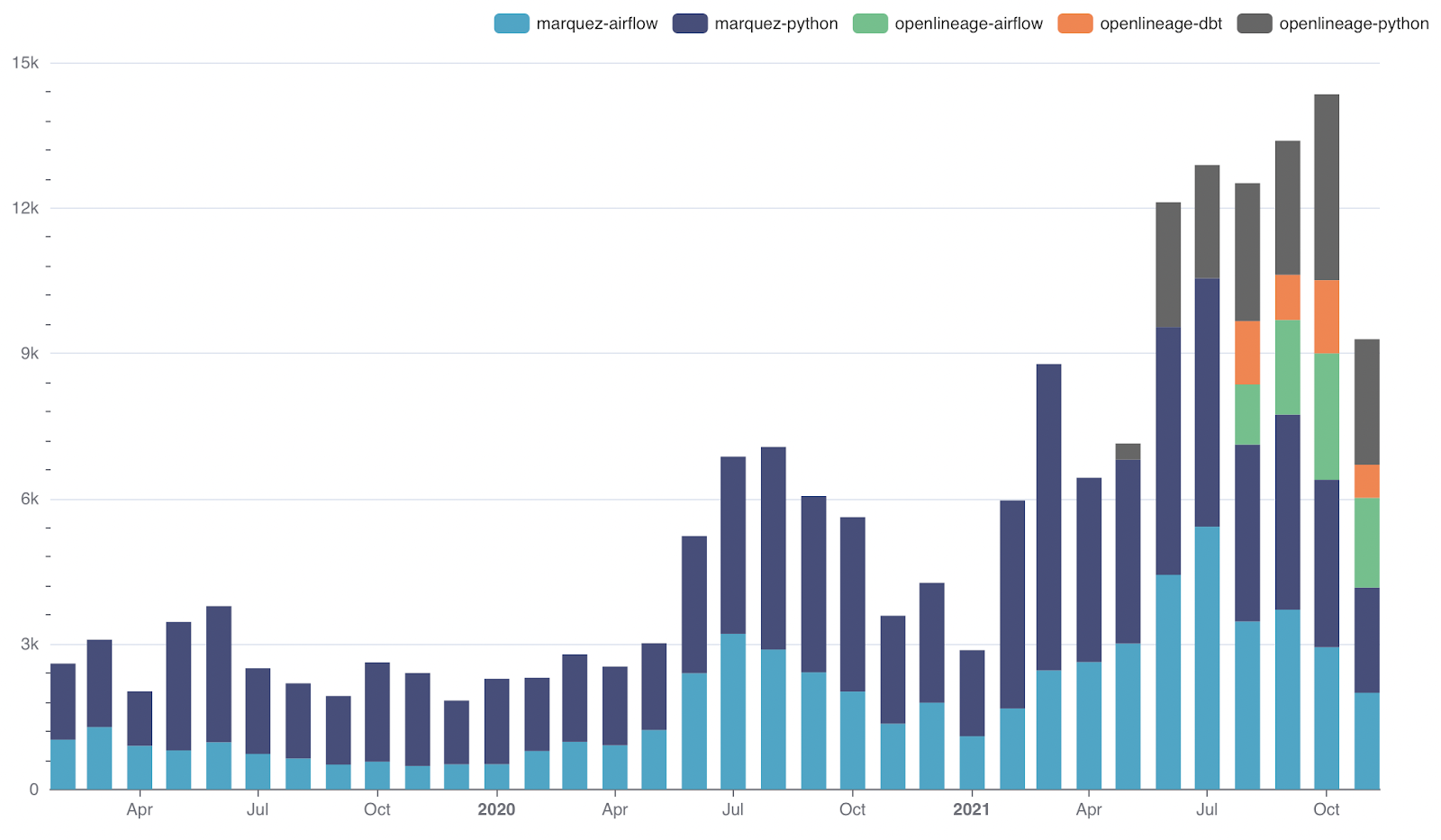

Something else can be learned from this PyPI data, something more specific to my project. Over the summer, several integrations were moved from the Marquez project to the OpenLineage project. That means that marquez-airflow has become openlineage-airflow. I'd like to know whether the old packages are still being used. When I create a chart using num_downloads as a metric and package as a dimension, with monthly granularity, it shows:

The shift began in August, and as of right now the Marquez packages still account for about half of the total downloads. That means we have some work to do. Likely there is some old documentation still out there to be found and updated.

What's next?

This is a very simple community metrics pipeline. Maybe this post should have been called "how to start studying community growth". Still, it contains all of the pieces of a large, complex one. Next, I plan to:

- Use Airflow (perhaps with the Astro CLI) to orchestrate the loading of data into

dockerhub_statsandgithub_stats, then trigger the necessary seed/run steps in dbt. - Look into creating some basic user segmentation - e.g., how much of this activity comes from people my employer sponsors?

- Expand the list of projects to include those we contribute to less frequently, so I can study possible intersections. Perhaps even include a few completely unrelated projects just for fun :)

To view the entire thing (including a Dockerfile I use to containerize it all) check out the OpenLineage metrics GitHub project, where pull requests are most welcome. I am easy to find - @rossturk on GitHub, Twitter, and dbt Slack - and am always interested in a chat about community metrics.

Comments